Zorbas and the Cosmopolitan Spirit of Skopje

Skopje has been an important city throughout its history. It was important for Ancient Rome, for the Byzantine Empire, for the rebellious Tsar Samuel, as well as for the medieval Serbian state which made Skopje it’s capital in the zenith of its power. Afterward, it was also an important city for both the expanding and the declining Ottoman state. After the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was formed in the first half of the twentieth century, Skopje was the southern capital of the compound state attracting residents belonging to different Balkan nations. On the track record of that history, Skopje became the capital of the newly established Macedonian national state after the Second World War.

The cosmopolitan spirit of the town attracted an ambitious entrepreneur and great hedonist of Greek origin. His amusing way of life, an incredible mixture of Mediterranean warmth, and Balkan joyfulness make him an icon for the big Greek artists who made him the emanation of the Greek identity, which became well-known globally.

The personal story of Jorgos Zorbas begins in the spring of 1922 when he arrives at the Skopje railway station from Thessaloniki (line-in function since the 1870s). He was carrying his youngest daughter, the ten-year-old Ekaterina with him as the only companion. He asked for the Lovec Hotel (on present-day Macedonia Street). He stayed in the hotel for the rest of his life. In the following years, the unusually big man with a characteristic mustache started his business adventure. He discovered a mine of decorative stone and arranged the rent, the exploitation, and the sales. He started making a profit, and at the same time, he began to earn his reputation as the biggest spender and hedonist in town. He became notorious for his Saturday parties in the local restaurants, especially in Marger and Kermes, the most famous in Skopje at that time. He would book the whole restaurant just for him and his friends. He generously paid the whole bill. And when the party echoed notoriously in the neighborhood, he invited curious passers-by to join his company and treated them. When the party was finally over, he would climb up the stairs to his room with the playing musicians accompanying him. They would follow him inside the room and then leave without turning their backs to him as if they were leaving a church.

Zorbas was a person with tragic family life, as his big love Elena died at the age of 35. They were deeply in love and had twelve children out of whom seven reached very old age. Jorgos was the son of the owner of a big herd of sheep from Northern Greece. They had a prosperous estate but the young Jorgos did not see himself as a shepherd and sheep breeder. He met Elena while working in her father’s mines. The boss of the mine was not happy to see one of his employees seduce his daughter. But Zorbas was decisive. He, in a way, hijacked the bride and they married in secret. Zorbas arrived in Skopje only with Ekaterina, but never remarried again. He found another great love in Skopje but never brought the lady to the altar. She was the beautiful widow Ljuba, attracting Skopje bachelors and bohemians.

Jorgos Zorbas’s life wouldn’t have become famous had he not met another great Greek, Nikos Kazantzakis, at the Piraeus port in 1915, during the First World War. They both wanted to try their luck at Mount Athos, but after a year each followed his own path. They promised each other to stay in touch. Four years later, Kazantzakis who in the meantime got employed at the Ministry of Social Affairs invited Zorbas to help him with the aid delivery to the Greeks living in the Caucasus. Thus, Zorbas became the Consul of Greece in Odessa. Zorbas confessed to Kazantzakis that he had lost his wife and considered it was time to fulfill his life-long dream to open his own mine. And so, he did. In the vicinity of Skopje, he opened the mine, made an access road, brought water, built a house, and started to work. He kept informing his friend of all his actions. They had a voluminous correspondence, which gave Kazantzakis sufficient material for his later novel.

In 1941 Zorbas died a sudden death of a heart attack just a few months after he arranged the marriage of his daughter into the Yada family of rich Jewish traders. Nothing else was known about the big bohemian until the film made Zorba a world hero. His original grave was transferred to Butel from Crnice after the Crnice cemetery was closed. His gravestone is still shining today in one of the corners of the Butel Cemetery decorated with the only known photograph of Zorbas preserved by his nephew Vangel. It bears witness to his extraordinary appearance and lifestyle.

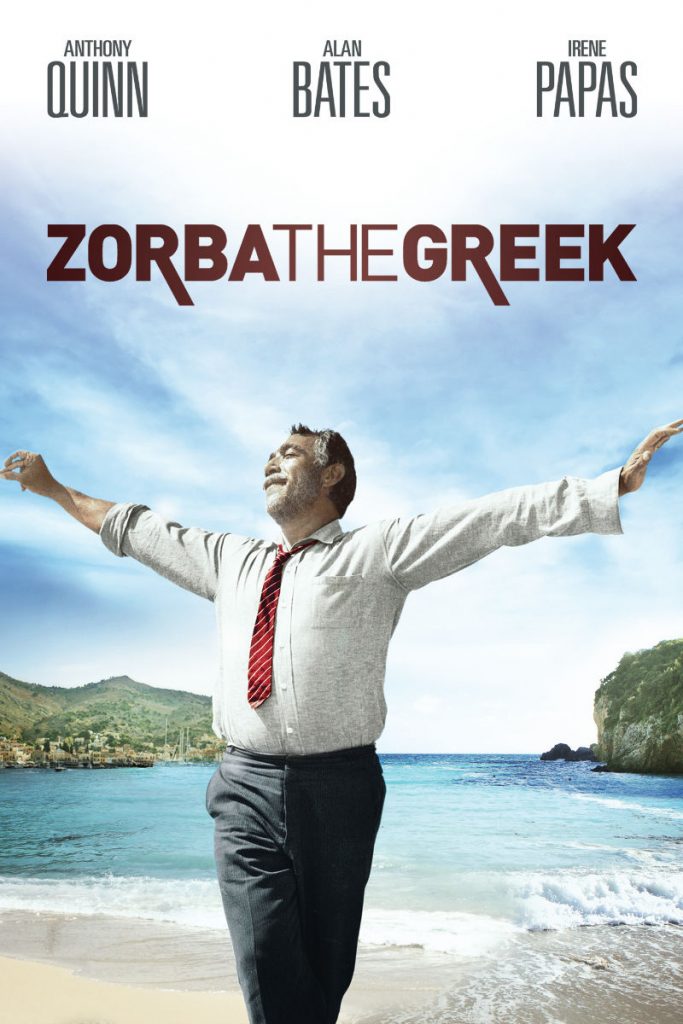

The international fame came to Jorgos Zorbas soon after his death. In 1946 his friend, the Cretan author Nikos Kazantzakis published the novel which he called Zorba the Greek: Life and Times of Alexis Zorba. To avoid disputes with the Zorbas family he changed the name of the main character and moved the action from Skopje to Crete, a place he knew much better than Skopje. It is the tale of a young Greek intellectual who ventures to escape his bookish life with the aid of the boisterous and mysterious Alexis Zorba. The novel was adapted into an even more successful film in 1964 by Cypriot author Michael Cacoyannis. The film featuring international stars won several Oscars. For this film, the Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis created a special dance based on the Greek melodies, which he called sirtaki. The music and the choreography of the dance soon became the most recognizable global cultural product of modern Greece. In 1968 Zorba musical was first performed on Broadway, and in 1988 a ballet of the same name was premiered in Verona, Italy.

In the mid-nineties the legendary Theodorakis staged and conducted the musical at the Macedonian National Theatre, to celebrate the improvement of the political relations between the two countries. One of the most important statements in the novel captures the essence of Zorba’s cosmopolitan’s views: “First I was distinguishing people as Greeks, Turks, Bulgarians, and Macedonians. Later I only considered them bad or good. Time is coming when I will not make even such distinction.”